I

The most unfortunate thing about Ingredients is its title. George Zaidan created a series for National Geographic, and so the publisher probably wanted to cash in on this a bit. The second most unfortunate thing is its subtitle: The Strange Chemistry of What We Put in Us and on Us. Sure, there are several short detours on the way sunscreen, cyanide, and formaldehyde work, but that’s basically it for chemistry. Ingredients is in fact Nutrition Scientists: What Do They Know? Do They Know Things?? Let’s Find Out!.

And so, you want to learn if processed food is bad for you.

Of course, you want not just that, but processed food is a good starting point, because a) people have recently started eating a lot more processed food, and b) people have recently started having issues with extra weight (especially in Polynesia). A natural conjecture is that these facts are connected, but to check it, you first have to define processed food.

Here’s one way people (Brazilian researcher Carlos Monteiro and colleagues) are doing it (it’s called NOVA classification):

- Group 1. Unprocessed or minimally processed foods (edible parts of plants, animals, algae; also eggs, milk);

- Group 2. Processed culinary ingredients (oils, butter, sugar, salt—substances derived from Group 1 foods or from nature by processes that include pressing, refining, grinding, milling, and drying—you probably won’t eat those by themselves);

- Group 3. Processed foods (add Group 1 items to Group 2 items);

- Group 4. Ultra-processed foods (basically everything else—soft drinks, snacks, sausages, etc.).

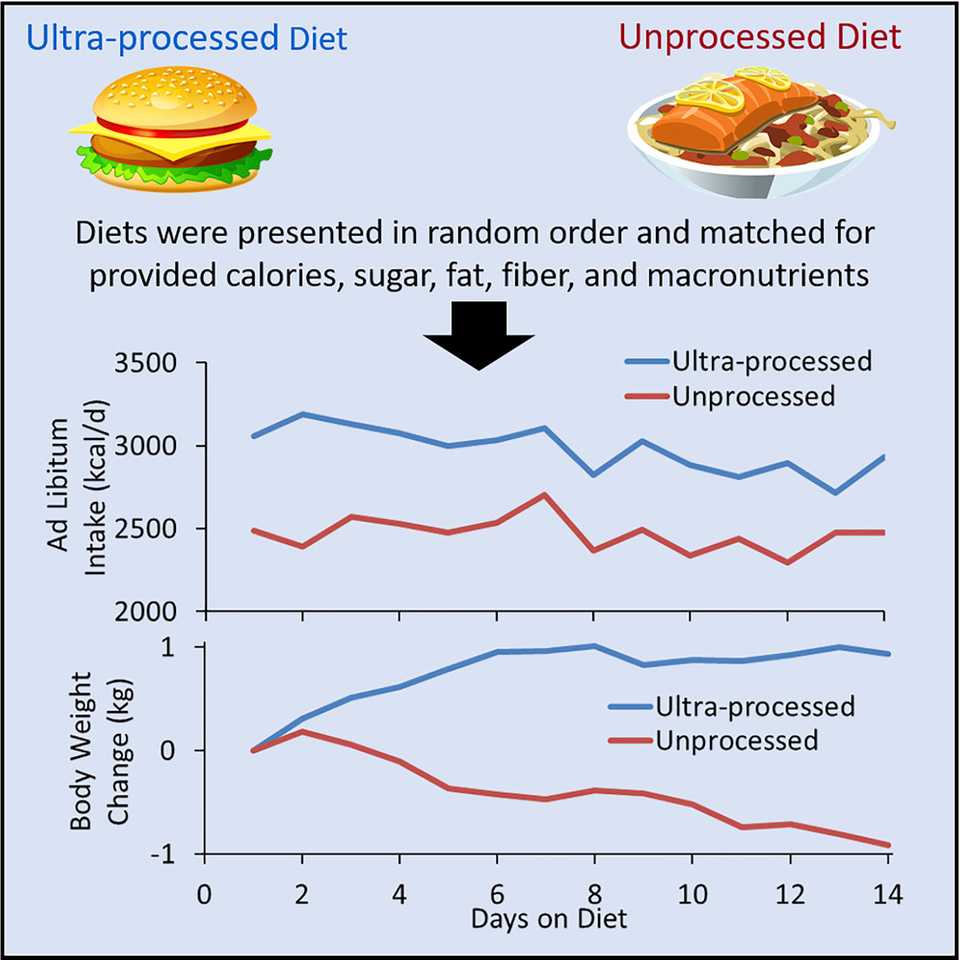

Oh boy. You can already see a lot of potential for lobbying, litigation, and unintended consequences if this classification becomes popular with governments (Can I add vitamins to my bread? Why are my soya extracts getting taxed?). However, this is good enough for studies, where you can just ignore grey areas and feed people either strictly broccoli with olive oil, or strictly muffins with crackers. Which is almost exactly what Kevin Hall et al. did: they got 20 people, split them into two groups, locked in a hospital for a month, monitored them closely, and got this graph:

(You could eat as much as you can, so ultra-processed food is either more energy-dense or tastier or both.)

Will this study generalise well? Let’s first get back to the book.

II

Ingredients’ first part is mostly about why do we process food at all, and this one is a part with most of the chemistry, with some botany added. Long story short: plants are cool, but they don’t want you to eat their parts, so they have to have some poisons, and also you may want to preserve some food for the future. If you are a knowledgeable Aymara person, you use clay or a complicated freeze-drying process to handle potatoes, and if you’re an ignorant westerner, you eat raw cassava and die. This part is fun (especially when you need to learn about poisons in a hurry) but doesn’t bring us closer to our goal, so the next two chapters are case studies in how do we know if we know anything about a) smoking; b) sunscreen.

Smoking is interesting precisely because it is boring: we are super sure that it causes lung cancer. We are extremely sure now because we have eleventy thousand studies showing that:

- There are chemicals in tobacco smokes, including nitrosamines.

- N-nitrosamines caused cancer in 37 different species in labs.

- Nicotine-derived nitrosamine ketone (NNK) caused lung cancer in rats, whatever the way you put it into them.

- The more NNK, the more cancer.

- NNK causes DNA mutations (which cause cancer).

- Repeat 2-5 for various other chemicals.

- Radioactive tracing shows that all these chemicals stay in your body for some time.

But even when we didn’t know that DNA mutations cause cancer, we could already tell that smoking is bad—basically just by looking at people. By looking at a lot of people (more than a million just in the US, although that probably was overkill, since all humans are rational and like facts more than tobacco ads), but still: if a person from group A is eleven times more likely to die of lung cancer than a person from group B, you don’t need fancy statistics. Related fun fact: lung cancer is a very twentieth-century illness—1898 and 1912 reviews of all known cases through the entirety of human history managed to scrape only 140 and 374, respectively (lung cancer itself was first described in the eighteenth century).

So smoking is simple (don‘t smoke; if you already do, stop or at least switch to vaping), even though we can’t run randomized trials. What about another source of cancer: the Sun?

Luckily, we already did an experiment here. This experiment is called “Australia” (convicts sent there were similar enough to Brits, but sun exposure is quite different, and so are skin cancer rates for white Australians—about 6.5 times higher than in Britain).

More seriously, sunscreen is much simpler than tobacco, because randomized trials are possible: you can ask people to use sunscreen (in a specified manner), and you can’t ask people to start smoking, so while with smoking we have to resort to observational studies, here you can do much better. Having said that, we weirdly haven’t done a lot of good experiments on the effect of sunscreen on cancer. Existing ones suggest that sunscreen adds some protection, but don’t explain the fact that over the past thirty years melanoma rates have tripled.

On the other hand, we know that sunscreen protects from sunburns, and we can even estimate a degree of this protection—this measure is SPF, of course.

Here’s how you could calculate SPF if you would like to receive approval for your new SPF 10,000 gel:

- Get a person with very white skin.

- Select a small area on their back.

- Apply a specific amount of sunscreen to that area.

- Apply various amounts of UV light both to that area and a control area on the same back.

- Compare amounts of UV required to give a slight sunburn in both areas.

If you need 10,000 as much UV to burn the protected area as for the unprotected, your SPF is 10,000 (in the real world, that would 30, 50, or 100).

Two more points: first, SPF 30 doesn’t mean that you can spend 30 times more in the sunlight as without it—both because of the way we define SPF and because you won’t have as much sunscreen as people are using in those studies (partly because of your clothes, sweat, and contact with various other objects in the world, and partly because humanity is stuck with a stupidly defined way to test sunscreens).

Second, there’s also an idea that if sunscreen doesn’t protect you that much from DNA mutations (and cancer), but stops your skin from burning, you’ll spend six hours a day in the sun instead of just two, and will get cancer precisely because of that.

III

Let’s get back to food. Why do we have a million studies showing that coffee increases the risk of any disease and another million showing that coffee decreases the risk for the same disease? (And the same situation for a lot of other things.) Half of those studies have to be wrong, so how did we get there?

Zaidan compares getting a real association between something and something to driving through a road full of potholes. Here are the potholes:

Pothole #1: fraud Pothole #2: basic mathematical mess-ups Pothole #3: procedural problems Pothole #4: Random Chance Pothole #5: statistical skulduggery, including p-hacking Pothole #6: confounded associations Pothole #7: study design

- Scientific fraud is fascinating, important, and dangerous, but also very simple (up to the point where you need to convince journals to retract those articles).

- Arithmetics is hard, not making typos in code is hard, using correct columns in spreadsheets is hard. Also, not publishing raw data is still the default approach, and that doesn’t help.

- Procedural mistakes are things like randomization of villages instead of individuals in a diet study (if water is bad in one of those villages, that will make one diet look a lot worse, through no fault of its own) and swapping variables for conservatives and liberals in a political attitude study (code and spreadsheets are still hard).

- There are thousands of way to misuse statistics. The most popular is p-hacking: if scientists can only publish papers with statistically significant results, and “statistically significant” means “get this number below 0.05”, many scientists will find a way to do this even if that means throwing the idea of search for truth out of the window. My shortest explanation of this particular problem: you can use statistical methods invented for testing a single hypothesis when you have multiple. (Maybe this effect is present for people older than 40? Younger than 25? University graduates? Danes? Danes older than 60 without a degree?). Try playing with this 538 simulation.

- Confounded associations are especially dangerous in food studies: people eating a lot of broccoli may be getting a lot of health bonuses not because of miraculous broccoli properties, but because they eat a lot of other vegetables, exercise, and don’t smoke. You can control for some of this (smoking is simple, other vegetables aren’t).

- Study design pothole in Zaidan’s book is just observational studies vs. randomized controlled trials, and it’s basically a continuation of #6—some confounding variables can be disentangled only using a randomized trial.

I left out #4 because to me it seems not just a pothole, but an enormous black hole just below the surface in the middle of our road to understanding nutrition. But before talking about it, let’s return to #7 for another chapter.

IV

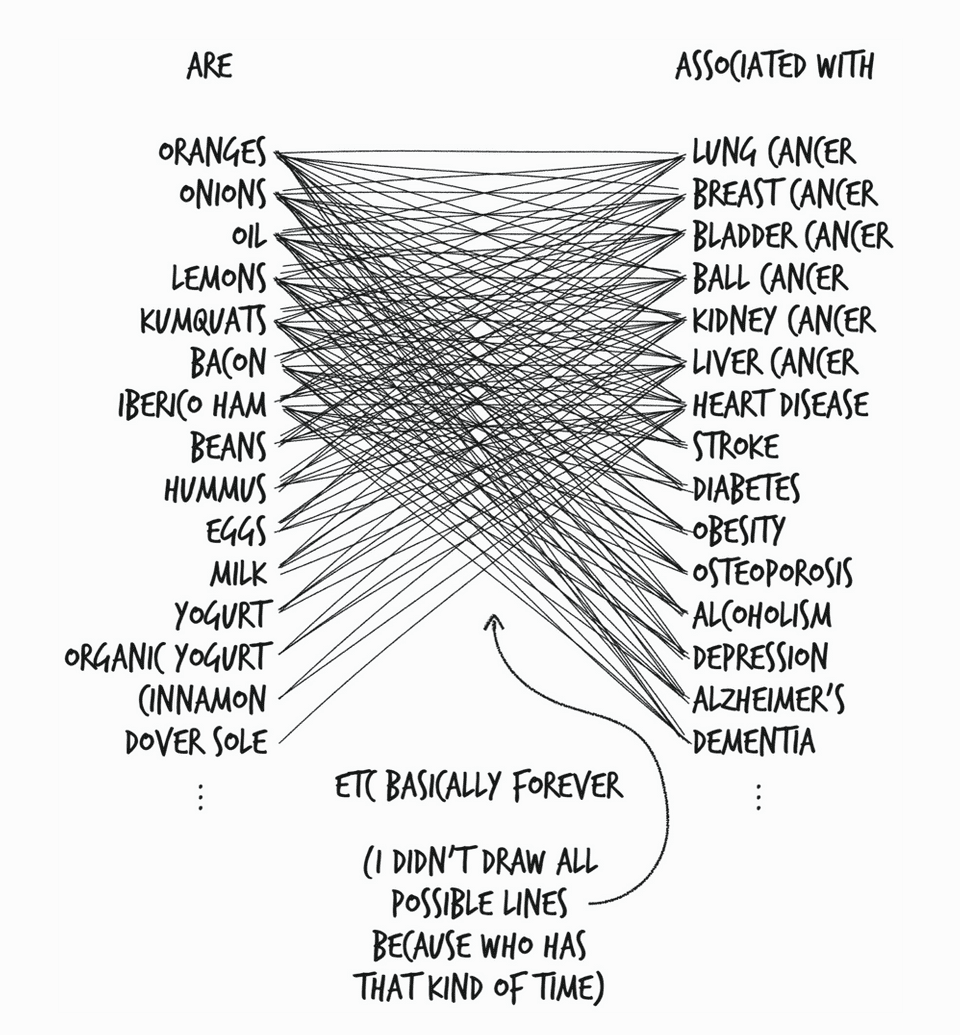

That chapter is John Ioannidis (the guy of “Why Most Published Research Findings are False” fame—and of much less inspiring recent fame) vs. the world of nutritional epidemiology. Here’s Ioannidis’ main concern, drawn by Zaidan:

There are hundreds of foods and hundreds of diseases, which means tens of thousands of hypotheses. Even 5% of those would mean hundreds of potential studies that will find enough statistical significance in all this noise to generate headlines like “Milk consumption associated with 15% higher risk of depression”. Worse still, you won’t be able to tell if milk causes depression (or if it’s actually broccoli that decreases the risk of heart problems) without additional randomized trials.

Epidemiologists’ response to this would be that a) we don’t do all these studies, only the ones that make sense biochemically; b) we also now do studies of whole diets, so instead of “broccoli” it can be “vegetables” or “Mediterranean”, which gets rids of some confounding.

Another Ioannidis’ concern is memory. People are really bad at remembering what they ate, and nutrition studies are really reliant on people remembering what they ate. NHANES, an extremely detailed study of 5000 representative Americans run every year, among other questions on health and nutrition, ask about their height and weight, and then measure their height and weight. Which means that we can study how wrong people are, which means that someone did this study, and of course, people are systematically wrong—men add half an inch and a third of a pound, women add a quarter-inch and remove three pounds.

Weight and height are simple. Remembering how many slices of pizza you ate over a year or even a month isn‘t—unless you eat pizza every day, but then you probably have difficulties with broccoli question—unless you never eat it. (Zaidan doesn‘t discuss whether regular journaling enhances reliability, but that’s probably a whole other subfield.)

Epidemiologists’ response to this would be “Eh, people remember enough for our purposes.”

Ioannidis’ response to all these responses would be “Get more money and run more randomized trials”. Epidemiologists’ response to this response would be “We now know how to fix many of the potholes (with pre-registration, open data, and similar processes), let’s try that first.”

V

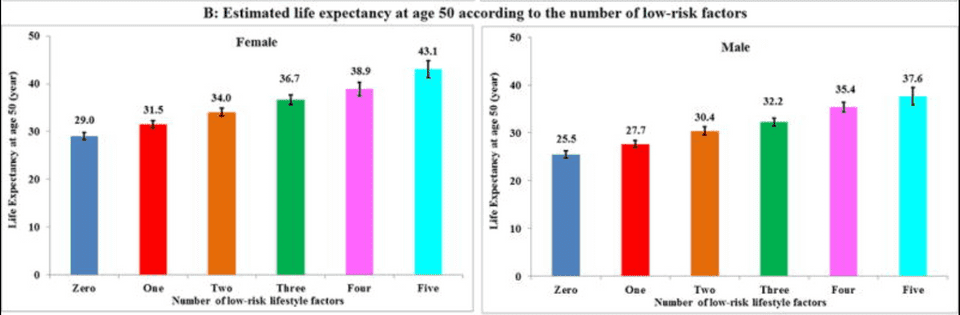

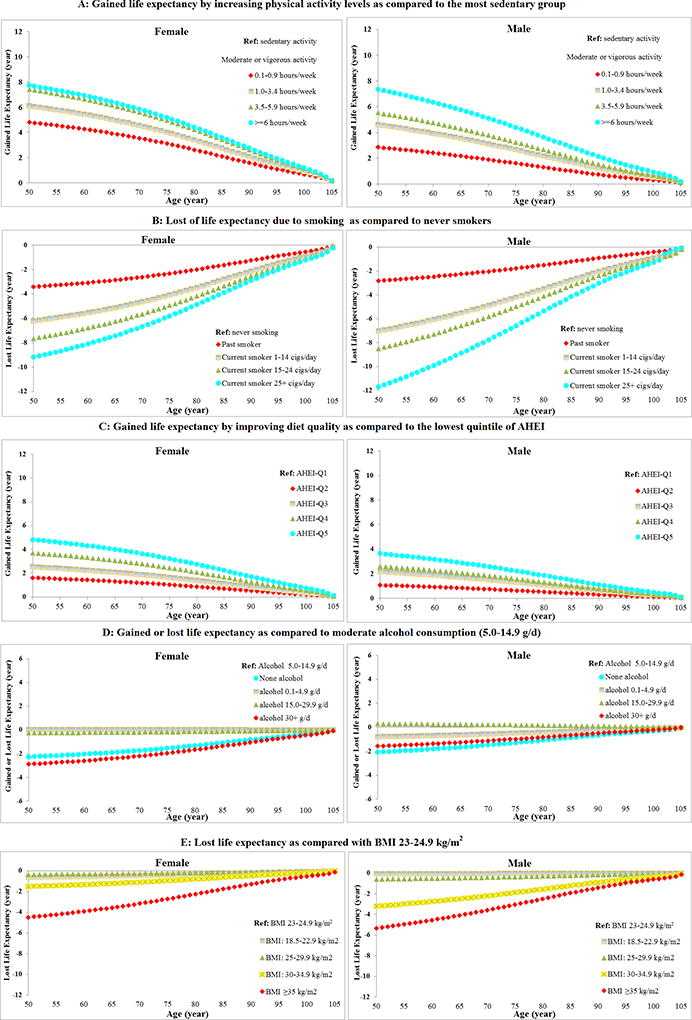

What should our response be? Zaidan brings up a study that compares the influence of several interventions on the life expectancy at 50 in the US (beware the man of one study etc., but the study itself isn’t the main point here). If you stop smoking, do 30 minutes a day of physical activity, don’t drink much, have a BMI of 18.5 to 25, and eat a quality diet, you are expected to live till 87.6 or 93.1 years (for men and women, respectively). If you smoke, don’t exercise, drink a lot, have a high BMI, and eat junk food, you’ll only get 75.5 and 79 years, respectively.

First, all these interventions obviously do quite a lot of good.

Second, smoking is by far the most important factor (especially for men), with only exercise getting somewhat close.

Third, sadly, you don’t get a straightforward sum of 10+8+4+4+5=31 from maximising all the stats, you get less than that (you get BMI bonuses from a better diet, you may smoke less when you drink less, etc.).

So on the one hand, diet quality is relevant even for the simple measure of life expectancy. On the other hand, it’s much less important than other interventions, despite putting all food changes into one basket.

What is a healthy diet in this study? “Lots of fruits, veggies, nuts, whole grains, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, and very little or no processed meat, red meat, sugary drinks, trans fat, and salt.” Nothing too specific, but with quite a lot of subpoints, with no single one making too much of change (and even these subpoints aren’t close to “Almond reduces the risk of heart attack by 14%”).

Which leads Zaidan to these four bits of advice to end the book:

- Don’t worry too much, mostly ignore news about the latest nutrition studies, sometimes check Cochrane.

- Don’t smoke.

- Be physically active.

- And the one about food is kinda hard to summarise, because in the end it seems anti-climactic: almost any non-snake-oil-diet recommended by a real doctor should be good enough (see above). And yes, if you worry about processed food, try cutting most of it—we don’t have evidence of it being a literal poison, but we also don’t think it’s actively useful.

VI

Here’s my main takeaway from Ingredients: nutrition science is in a bad place, and I don’t see getting much better even if it can fix with p-hacking. Its main problem isn’t badly conducted studies, its main problem is noise.

I don’t expect that we’ll find many more things similar to vitamins—something with quick and strong effects that can be studied in a short randomized trial. Even enormously-powered extremely long studies of a single food effect on a single disease won’t give you a strong result—we have grabbed almost all low-hanging fruit.

Instead, what I would like to see is a book called Actually Ingredients: What Happens to the Cells and Molecules of Pork When We Turn It into Carcinogenic Bacon. We don’t know enough about how our organisms work differently with different types of food, and we should. Asking people for 50 years what they ate yesterday won’t work (even if they only eat food that already existed at the beginning of the study), but asking their, synthetic, and mice stomachs might be what we need to understand Cheetos.