Non-fiction

The best book I’ve read this year is Science Fictions by Stuart Ritchie. It’s a concise summary of current problems in science (fraud, broken publishing, overhyped results, replication crisis in psychology, you name it) with a chapter on solutions that aren’t utopian (many of those are already being implemented).

George Zaidan’s Ingredients can be read as either a shorter introduction into many of the same issues or as a follow-up focused on nutrition science. Nutrition science may be in an even worse shape than psychology, simply because studying nutrition is hard: trials are expensive and difficult, effects are very small and may not appear until decades later, and desire for simple explanations is enormous. I’ve written a longer review here.

How to Make the World Add Up by Tim Harford is related to the previous two books, but instead helps to understand what can be done about this not when science is fully reformed, but right now, when data is dodgy but you still have to decide whether to be outraged. Read the sources, check what exactly is being counted, don’t forget about standard biases.

Robert Sapolsky’s Behave is, on the one hand, a useful amalgamation of various topics he has written about before, but, on the hand, is a minefield in its chapters on psychology (this didn’t replicate for sure, this probably did, this will have to be checked when I come home). I still recommend his Stanford course (fully available on Youtube), but watch out for references to studies that might have aged badly.

You might have noticed that socialism and communism are popular again (or you might have watched some TikToks and decided that all those Eastern Europeans post-punk bands are singing about how great it is to live in Khrushchyovkas; they don’t and it’s not). Kristian Niemietz’s Socialism: The Failed Idea That Never Dies inoculates against an idea that “It just hasn’t been properly tried”. First, Niemietz talks about features inherent to socialism that lead to a state becoming an evil dictatorship (you need to concentrate power for centralised planning, you can’t let people out if you want those plans to work, oh, and also now you’re poor because without prices—that is, without decentralised knowledge—you have no idea what you’re doing). Second (and that’s the bulk of the book), he goes country by country (USSR, China, Cuba, North Korea, Cambodia, Albania, East Germany, Venezuela) and shows how Western commentators get extremely excited every time—“you told us it couldn’t be done, and now look, here’s Stalin/Mao/Chávez leading his country into greatness”—right until a honeymoon period ends, and it’s death camps and killing fields all over again, at which point they all go back to ”of course, it wasn’t real socialism, if only, if only.” Here’s the whole book in PDF.

Maoism: A Global History by Julia Lovell is, well, a history of Maoism—both in China and as the export to dozens of countries in Asia, Africa, and America (despite anti-imperialistic proclamations). I didn’t know there is an active Maoist insurgency in India.

Anne Applebaum’s Iron Curtain, on the contrary, focuses on just three countries: East Germany, Poland, and Hungary. How do you go about making a country communist if a country doesn‘t want it (and, weirdly, rape and pillaging didn’t help)? Secret police, control of mass media, the disintegration of all independent organisations, and a little bit of ethnic cleansing.

Where Is My Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall tackles this question as non-rhetorical one (and as a symbol of technological stagnation). To me, an idea of The Fifth Element-like flying cars seems to be a complete non-starter (even if all of them are being piloted by AIs, I prefer not to have a risk of a car crashing into my window), but Hall’s vision is basically a plane that goes to nearby cities without spending hours on driving to and from the airport and security theatre there. In the mid-twentieth century, people have built a lot of prototypes in this vein, and technological obstacles (e.g., we would have to completely revamp and automate flight dispatcher system) are serious but not insurmountable, so what happened? Hall’s main answers are bureaucratisation, regulation, and tech pessimism (all of which can be applied to the overall stagnation):

Unlike a century ago, today for everyone who is working on advancing technological progress, there is someone else who fervently believes that they are saving the planet by stopping them.

Jason Crawford wrote a longer review of Where Is My Flying Car?.

Infinite Powers by Steven Strogatz is a great popular book on (the history of) calculus, mostly because instead of dumbing down the mathematical parts, Strogatz reworks explanations from original authors (who themselves relied a lot on words instead of formulas).

Open Borders: The Science and Ethics of Immigration by Bryan Caplan and Zach Weinersmith does a good job explaining why we need much more immigration into wealthy countries (with completely open borders being the simplest solution for this).

Fiction

Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, despite what many reviews might be saying, tells a pretty straightforward story but does it in the most precise English I’ve read in years. You don’t need to know much about Piranesi, but it’s useful to take a look at his Imaginary Prisons before starting the book. Clarke’s chronic fatigue syndrome is a tragedy.

For some reason, every post about Gideon the Ninth should use the phrase ”lesbian necromancers”, even though the fact that those necromancers are lesbian is the most boring thing about this book. It’s a well-written mix of sci-fi and fantasy with nicely-executed switches between styles and genres and good characters, and if those characters wouldn’t care much about the word “lesbian”, you probably shouldn’t as well. Harrow the Ninth, its sequel, suffers from let’s-dump-half-of-the-plot-into-the-last-ten-pages syndrome even more than the first book, and I probably need the trilogy conclusion (planned to come out in 2022) to understand Harrow properly.

After finishing four seasons of The Expanse I found out that there are five more books in the series, so I decided not to wait for additional seasons. Those are good novels, even if the further it goes, the more they are books about characters, not about politics of space exploration. (The situation on Earth doesn’t make any sense, however: it has 30 billion people (???), and the majority of them are unemployed—but even simple stuff like asteroid trawling is still being done by humans, not by robots, and there are still evil multinational companies that presumably have to hire not only evil scientists). The final novel is due out in 2021 and will be the only US novel I‘ll read this year.

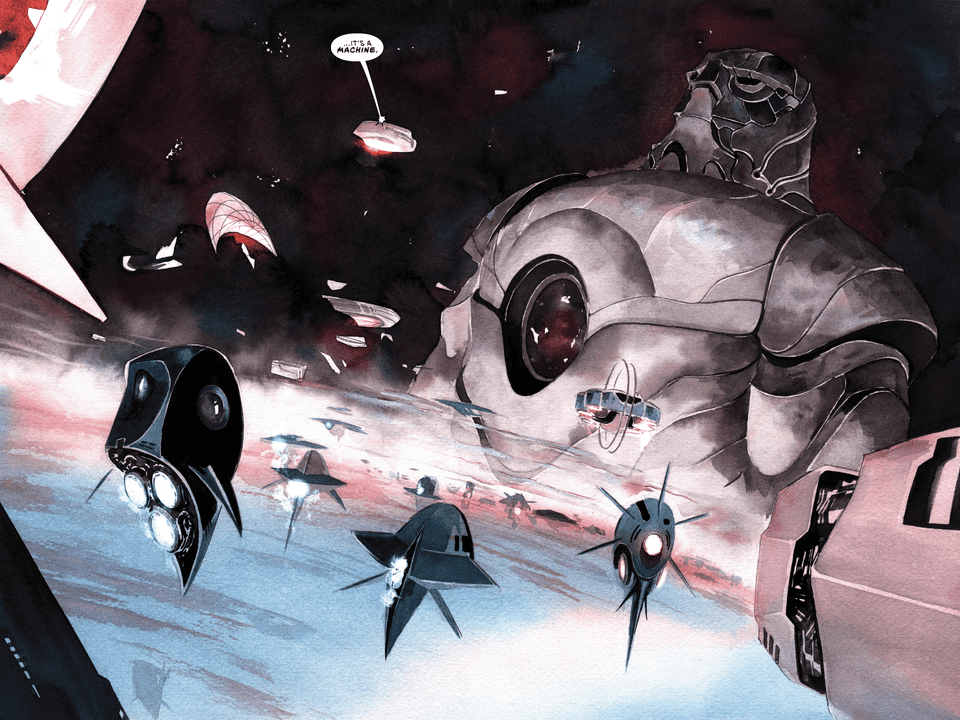

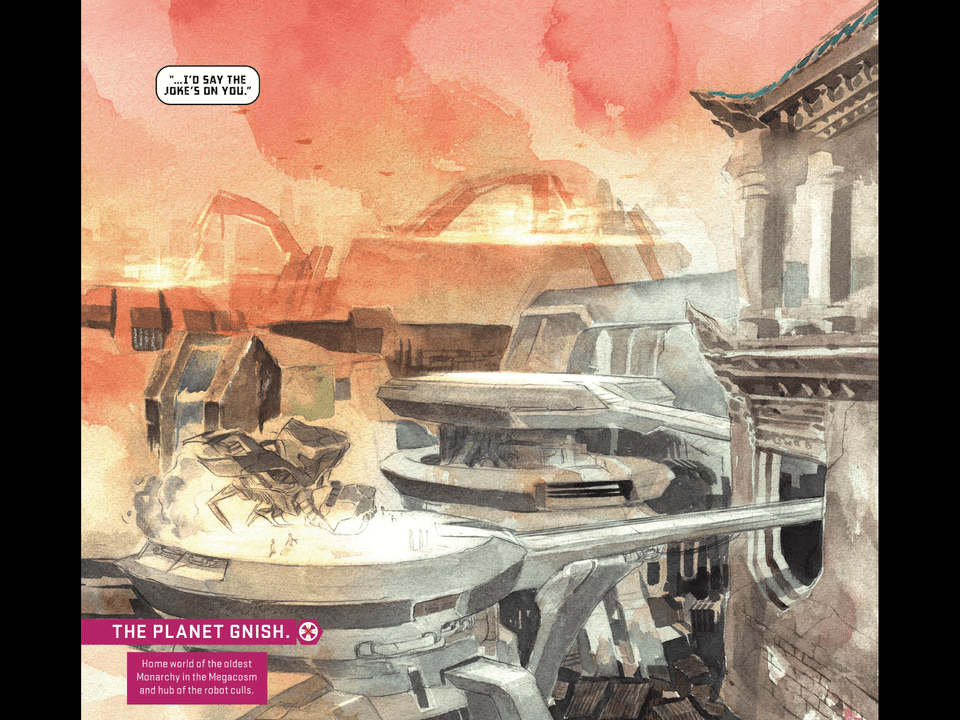

Descender by Jeff Lemire and Dustin Nguyen is similar to Saga in having a rather bland sci-fi story that mainly an engine for the artist.

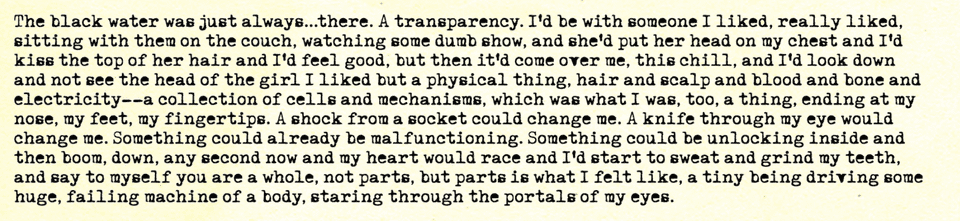

Another book by Jeff Lemire (with Scott Snyder), A.D.: After Death, despite belonging to the standard boring genre of ”Long lives are bad for yet another reason”, has good moments, including this one (it is text-heavy throughout):

Monstress is still the best ongoing series.

Hoped to like more

I liked a lot of Freddie deBoer blog posts (including Planet of Cops that isn’t on his blog anymore, yet remains extremely relevant), but The Cult of Smart seemed weird to me in two ways. In short, it’s a book about blankslatism in education in the US and the way only intelligence is valued there (which I don’t think is true anyway, both in a good and a bad sense). First, as is too common in books about problems, the supposed solution is nothing less than a full revolution. Can a society decide that you don’t need a college degree or a license to be a hairdresser without changing much else? Probably yes, and also you could sell this change to people who don’t like socialism (or any other kind of utopia that’s usually being built in the last chapter of a Book on an Important but not All-Encompassing Issue).

The second issue is related to this: I find extremely surprising (especially for a leftist author) that deBoer completely ignores other countries. Maybe if you look at Germany and find that it’s better at something while being similar to the US, you don’t need to reform every single thing about education to fix a specific issue? Maybe you still think that without socialist revolution education will remain awful, but this revolution won’t happen any time soon, and a simple change could improve someone’s life immediately.

Annie Duke’s How to Decide would have been a great 100-page book, but instead, it is packed with business-book-like exercises that don’t add anything, especially in the dragged-out middle chapters.

The Emperor of All Maladies is supposed to be the book on cancer, but is mostly a history of medical oncology in the US.

How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe was great, and I was excited about Charles Yu’s latest book, Interior Chinatown. However, a very Yu-like (Yuesque?) premise (main character both plays a Generic Asian Man in a procedural TV show and perceives himself as one in his life—while having aspirations to become a Kung Fu Guy; it’s written as a scenario that intermingles real life and the show) goes basically nowhere. It received a National Book Award. Please read How to Live Safely.

Please don’t read the Dune sequels (both written by Frank Herbert and by his son Brian). Instead of getting richer, the world just falls apart. Instead of an introduction of interesting new characters, the old ones get resurrected. Instead of reading the sequels, check out Bret Deveraux’s blog posts on the Fremen Mirage.

You can follow me on Goodreads. This year I hope to write regularly at least short book reviews.